By: Robert L. Smith

Some, including myself, would like to see more substance over style in recognition of Black History Month and its celebration. In other words, what can we learn from the past that is critical to changing society in real ways that affect the health, education and welfare of our people while leveling the playing field and mitigating the effects of income inequality, systemic racism and white privilege on our daily lives?

We can make Black History Month more meaningful by chronicling the stories that provide critical insight into past events. We can analyze what we’ve learned from this history that can empower people and communities to overcome the historical oppression of the past, and in these ways, we take control of our destiny.

Briefly, to this point, are illustrations of a historical narrative that illuminate the importance of telling meaningful stories and learning from those stories as they apply to life today within the context of Detroit’s African American History.

One historical myth is that Black people migrated to Detroit because of the $5.00 a day job at Ford Motor Company; however, a closer look at this historical development reveals different motivating factors for both Henry Ford and Black migrants themselves.

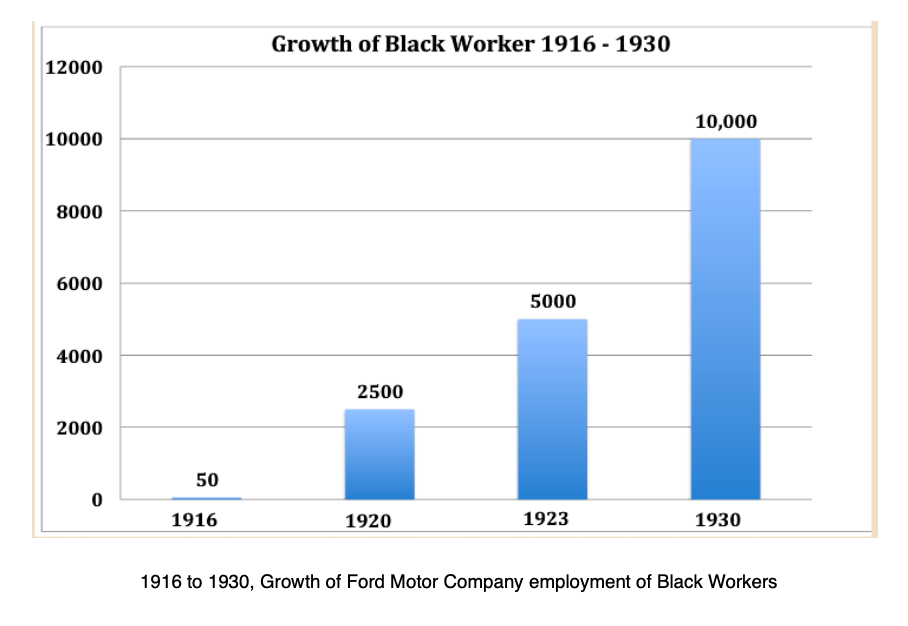

In 1914, Henry Ford decided to pay his workers, through a profit-sharing plan, $5.00 a day to stabilize a volatile workforce. When he makes this decision, his workforce of 14,000 at his Highland Park plant is 75% white foreign-born. At the time, Ford, like all automobile manufacturers, refused to hire Black people. From 1914 to 1917, Ford only employed about 200 Black workers, mostly janitors, out of 15,000 workers at his Highland Park plant.

By 1917, the first significant migration of African Americans from the South is well underway, with 25,000 blacks arriving in Detroit. At this time, other than a few janitors, Ford does not hire Black employees; therefore, we must conclude the notion that Black workers came to Detroit because of the $5.00 a day job at Ford is not entirely accurate. A closer look reveals racism is pushing Black families out of the South and they are not coming North solely for jobs.

Black families are leaving the South because of oppression and racism. The generation that is coming are the children of enslaved people. Unlike their parents, they are unwilling to tolerate the lynching, the denial of education, basic decency and respect in their daily lives, so they head to Northern cities, including Detroit.

However, in 1917, Ford dramatically changed his exclusionary hiring policies, not for altruistic reasons, but purely for economic gain. Ford is challenged with building the massive Ford Rouge Plant, his growing debt to minority stockholders, the formidable IRS, and his mostly European immigrant workforce is pushing for unions.

Fearing a loss of control over his workforce, Ford turns to Black and white workers from the South. Ford would come to view Black employees as the ideal workforce. Black residents needed jobs; they had no interest in unions because white unions had excluded them, so in the 1920s, Ford began to hire Black workers in large numbers.

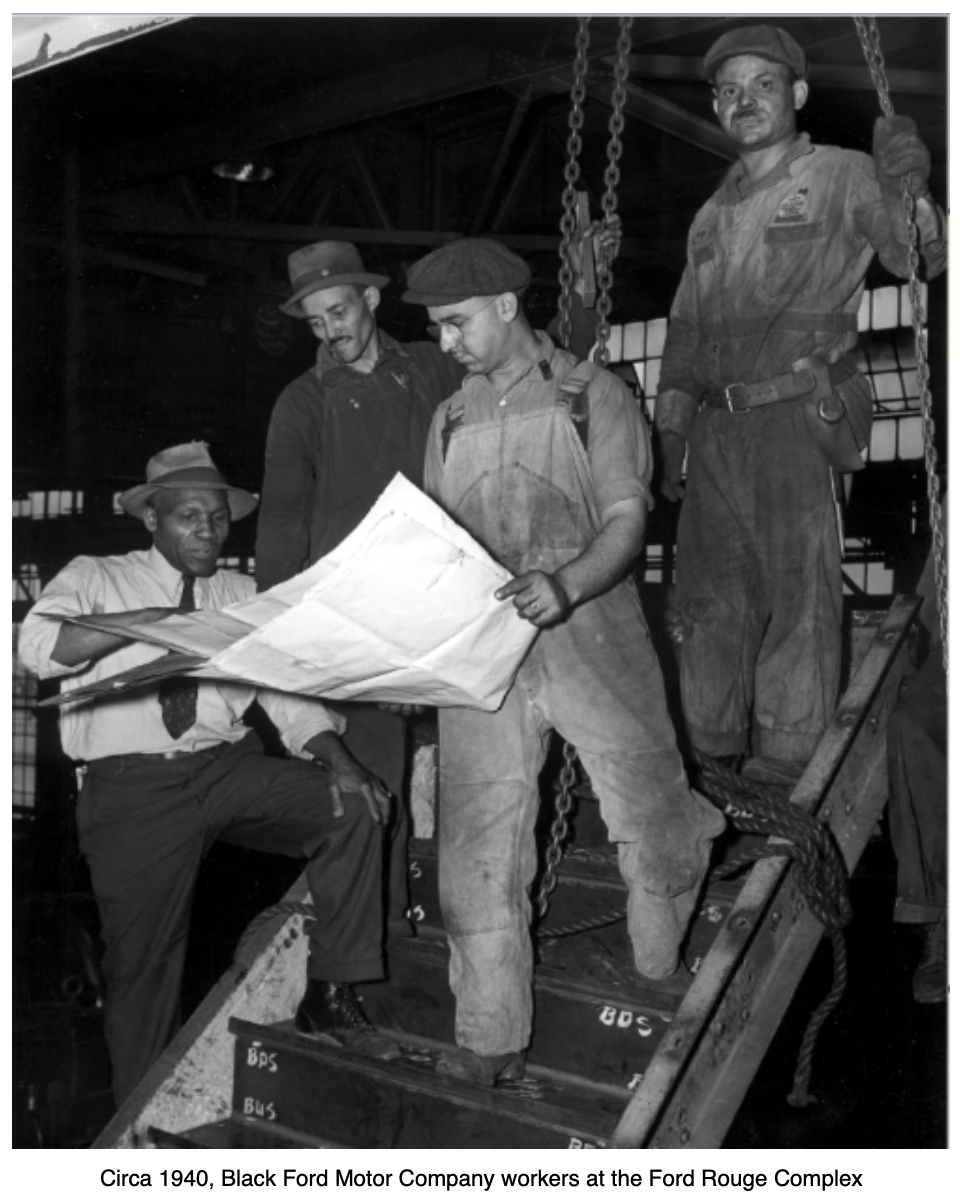

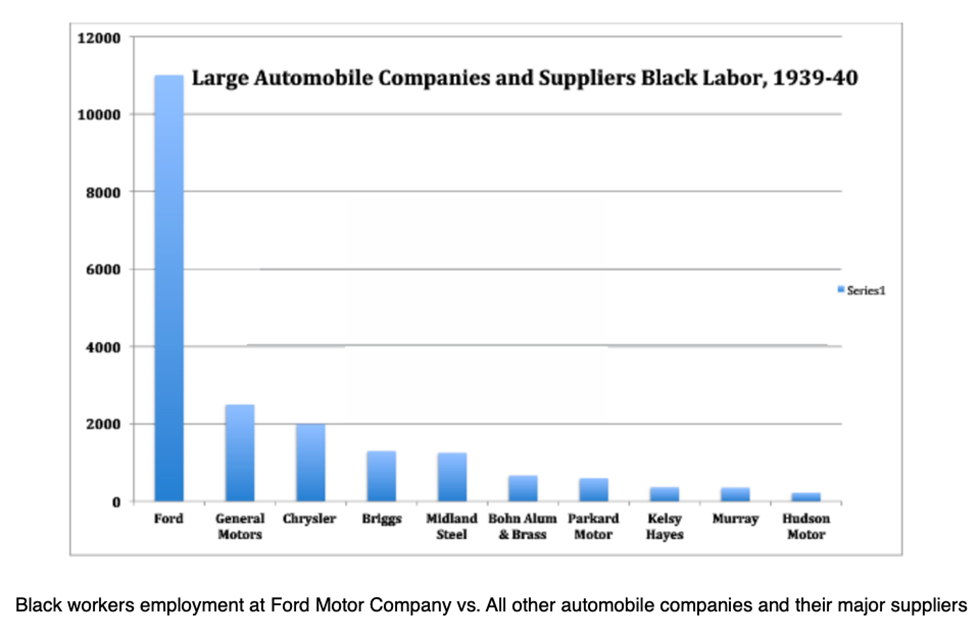

By 1930, 100,000 people work at the massive Ford Rouge plant, and 10% (10,000) are Black. There are more Black employees at Ford than all of the other automobile manufacturers and their suppliers combined. With no formal education, Black Detroiters are probably making more money at that time than their peers around the world. Moreover, this workforce attracted other Black professionals from around the nation to Detroit, black lawyers, doctors, dentists, and educators, and as a result, there was the development of the Black business community – Paradise Valley. So, Ford’s business decision has a historical domino effect.

While this was progressive, the opportunity to obtain a job at Ford did not translate into a long-term wealth opportunity for the African American community as it did for white European immigrants and whites from the South. Ill-educated whites from Europe and the South were able to invest part of their wages from their auto jobs into buying their family home. In Detroit, from 1923 to 1928, 50,000 new homes were built in the city of Detroit proper for white auto workers. Realtors refused to sell or rent any of these homes to Black residents. Black people in Detroit, regardless of their income or professional status, could not obtain a mortgage. For example, a white worker from Ford could obtain a mortgage before a Black schoolteacher could. Black workers were making more money than they had at any other time or place on earth; however, they could not obtain a mortgage for a home and build long-term wealth for their families. This provides us with insight into how businesses can have a powerful effect on addressing historical injustice.

On a smaller scale here in Detroit, the massive challenge still exists of providing an undereducated population of African Americans with good-paying jobs. If left unchecked, history will again repeat itself with the opening of the new FCA plant on Detroit’s eastside and the promise of nearly 5,000 jobs. Like the auto industry of the past, this project will bring suppliers and factories to the city, creating more jobs and the potential to spawn new business development.

However, without long-term vision and understanding history, FCA and similar ventures could, without intervention, stymie generational change. What is the vision for the eastside in housing, education, healthcare so this opportunity changes lives for the long-term?

I know personally how historical events can have long-term consequences and impact future generations. My father served in the Navy during World War II. In 1947, he came to Detroit from Mississippi; his family had been sharecroppers, cultivating cotton. He obtained a job at Chrysler Corporation, and for more than 30 years worked at the Jefferson Avenue plant. He married and had seven sons. Our family resided on the lower eastside of Detroit, a few blocks from the Belle Isle Bridge. Under our mother’s guidance, my brothers and I all attended the Detroit Public Schools and completed high school and went on to college. Today, my brothers and I are nearing retirement. We have led very successful careers as an OB-GYN, an engineer, a dentist, an artist/museum specialist, an educator, and building contractor. Our oldest brother died in Vietnam (Navy) serving this nation. All of our children have attended or are currently attending some of the leading colleges and universities in the nation. This was primarily made possible due to the opportunity our father had employed as a factory worker in the mid-1950s. The story of my family is not unique but was repeated throughout Detroit during the Post World War II period, and it is a historical narrative that provides a vision for the future.

Robert L. Smith is currently an independent contractor of historical media products and programs. He is currently under contract to research and write for HistoryMakers, the nation’s largest digital archives. From October 2006 to July 2014, Smith was employed by the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, leaving as their Vice President of Education and Exhibitions. In this capacity, Smith has directed the production of an array of exhibitions on African American history. In between his professional positions, Smith worked as a free-lance instructional designer. From 1997-1999, Smith directed the Damon J. Keith Law Collection at Wayne State University and completed a traveling exhibition, Marching Toward Justice: which brought Wayne State national recognition. From 1997 to 1998, he directed the African-American Media Society and produced The Calling and the Courage, the History of African American Education.